Why read this article? Learn about how City Mission Societies:

Were the predecessor to rescue/city missions

Established foundational theology and values informing today’s movement

Provided a comprehensive social safety net that formed the prototype for government initiatives

Had most services displaced by the modern welfare state, leaving today’s rescue missions focused primarily on evangelism, homelessness and addiction

Don’t have time to read this? Listen to the Podcast on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Others

How City Mission Societies Formed the Basis for the Rescue Mission Movement

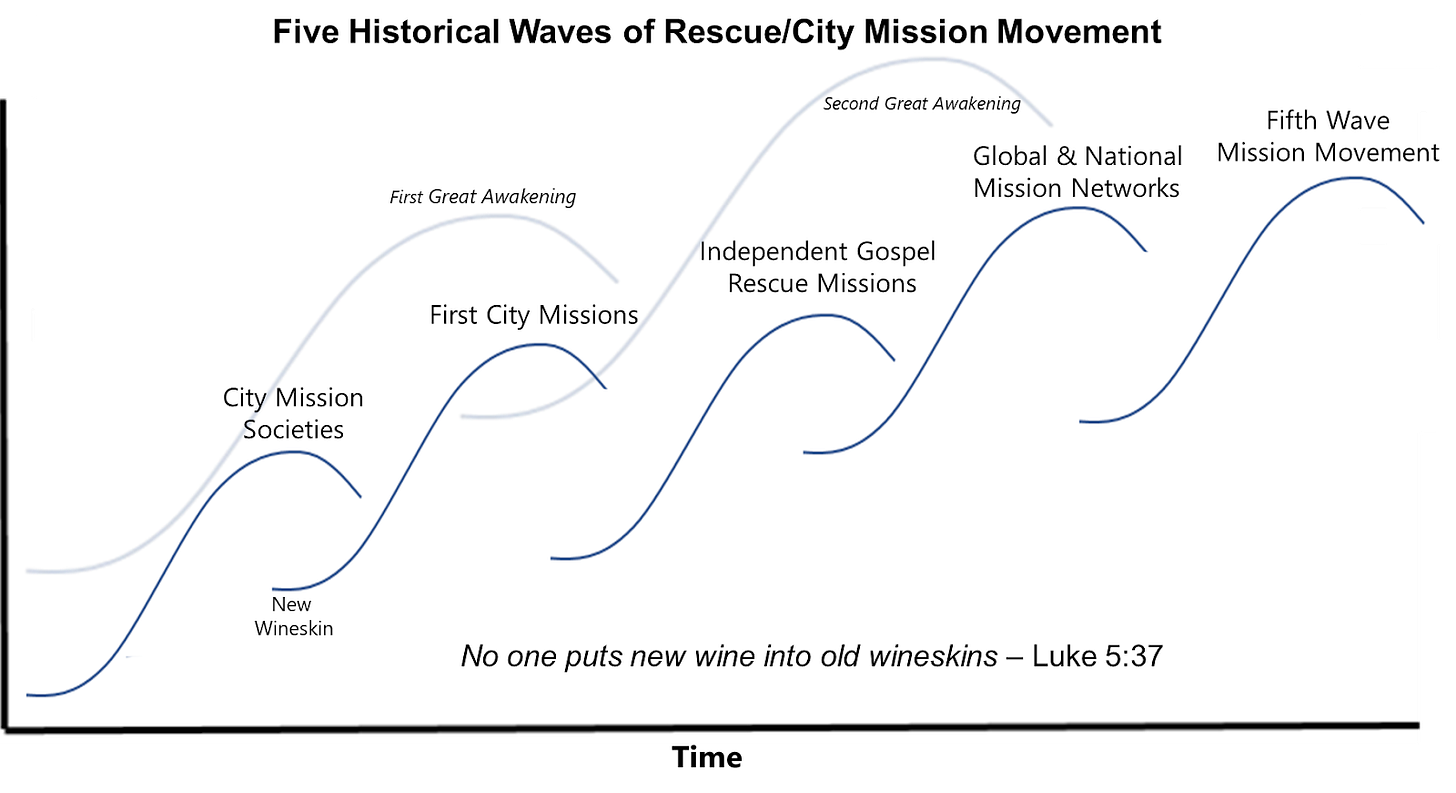

This article starts a new series on the five historical waves of the city mission and rescue mission movement. We hope to eventually turn this series into a book that will review the past and current innovations to determine emerging features of what we call the Fifth Wave of the movement.

Movements, like the rescue mission and city mission movement, face the same lifecycle and need for innovation and new wineskins as society changes. The history of missions is filled with examples of groundbreaking models that, in their time, were radical innovations. Yet, as societal needs shifted, some of these models became less effective, either adapting to a new reality or fading into irrelevance. The rise of the welfare state, growing complexity of mission work, changes in homelessness and addiction, and challenges of secularization are just a few of the massive shifts that have challenged the church to rethink how it does ministry.

The diagram above shows the five historical waves of the City Mission/Rescue Mission Movement. In this article series, you’ll learn how each of these waves where each represents a major innovation extension or ministry recontextualization:

The City Mission Society

The City Mission

The Gospel Rescue Mission

Global and National Networks

Fifth Wave of the Rescue/City Mission Movement

In this article series, each stage will be analyzed as a distinct innovation, demonstrating how it emerged from specific historical pressures and was adapted from its predecessor, creating a clear lineage of ministry development. You can see a more complete lineage in the City Mission/Rescue Mission Family Tree here.

This article dives deep into the “first wave” of the city mission and rescue mission movement: the City Mission Societies of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This isn’t just a history lesson. It’s an excavation of a forgotten strategic genius—a blueprint that combined fervent piety with sophisticated social engineering, and one that holds profound lessons for our work today.

Roots in The Great Awakening and Missionary Societies

This article argues that the city mission and rescue mission movements were just one of many moves of God that emerged from the First and Second Great Awakening (shown in the 5 Historical Waves diagram above).

While the First Great Awakening occurred primarily in the 1730s and 1740s, the fruits of such major revivals are often felt in religious vitality for decades and sometimes centuries. The article The Rescue Mission Movement: A Case Study in Revival as Systemic Change explores this idea of how the Great Awakening helped create the City Mission and Rescue Mission Movements. One model we use to describe this in our courses is the Systems Thinking Social Ecological Model for Rescue/City Mission Movement where revival creates religious vitality at the macrosystem level that then spawns movements, organizations, deepens relationships and transforms individuals both internally and behaviorally.

One aspect of this continued growth was an was an increased zeal for the lost globally, which culminated in 1792 with the founding of the Baptist Missionary Society as the first Foreign Missionary Society and the modern missionary movement, inspired by the powerful writing of William Carey, whose Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathen (audio summary) became the movement’s charter. As the foreign mission movement was gaining momentum, it then spawned the first Domestic Missionary Societies.

The World That Birthed a Movement

To understand the innovation of the City Mission Societies, we must first picture the world they entered. The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a time of massive upheaval. The Industrial Revolution was creating burgeoning cities plagued by exploding problems: unprecedented poverty, spiritual emptiness, and what observers called a growing urban “godlessness”.

In the face of this crisis, the established church was often found wanting. Whether in Britain or America, the official church was frequently too slow, too rigid, and geographically disconnected from the burgeoning slum populations where help was needed most. It had become formal, stale, and impersonal—incapable of effectively engaging with the sheer scale of the need. This created a landscape of huge material suffering alongside vast spiritual apathy.

This new zeal demanded a vehicle, a structured outlet to carry the gospel into the chaotic city streets. That vehicle became the City Mission Society, as an urban counterpart to domestic missionary societies. And that necessity brings us right to the core structural innovation: the City Mission Society model itself. The City Mission Society is the key invention that let this new spiritual energy become a strategic, sustainable movement. It was an act of profound entrepreneurial genius applied to charity. The core innovation wasn’t a new kind of soup kitchen or a building; it was setting up a strategic, non-denominational coordinating body. Crucially, it wasn’t just one church deciding to help its neighborhood; this was a coalition of concerned pastors, civic leaders, and lay leaders coming together to look at the needs of the entire city region, transcending parochial boundaries and, importantly, denominational divides.

The Architects of Transformation: Chalmers and Wichern

This movement was guided by brilliant thinkers who provided its philosophical and theological backbone. Thomas Chalmers (audio summary), a pastor in Glasgow, turned his parish of St. John’s into a world-famous “laboratory” for applied Christian economics. His core principle was “locality”—the belief that the impersonal, sprawling city had to be broken down into small, manageable districts where personal relationships could be built. But his most challenging and influential idea was that of “discerning personal charity”. Chalmers was fierce in his opposition to indiscriminate giving and government-run “pauper relief,” which he saw as “morally corrosive”. His radical method involved eliminating all legal parish relief and replacing it with a system of voluntary deacons who knew the families personally. They administered material help only where moral failure was not seen as the primary cause of poverty.

For Chalmers, the goal was not just to feed the poor, but to reform citizens. He believed his morally focused approach would produce a “more erect and honorable and high-minded population”. He saw dependency not just as a lack of resources, but as a failure of character and community responsibility, a vice fostered by careless charity.

One of the early pioneers of this new message was Greville Ewing (audio summary) who was consumed by zeal, laboring tirelessly, traveling constantly, utterly convinced that their organized efforts wouldn’t be wasted because they served a gracious master who expected them to act. Thomas Chalmbers and Greville Ewing both lived in Glasgow, Scotland and served as leaders of major evangelical secessions from the Church of Scotland in different denominations. Greville Ewing served as pastor to David Nasmith, the founder of the City Mission Movement.

While Chalmers provided the micro-strategy, Johann Hinrich Wichern (audio summary) in Germany provided the macro-vision for the German counterpart of the City Mission. He championed the “Inner Mission,” a comprehensive, coordinated national network of Christian social work. His goal was nothing less than the “re-Christianization” of the German people and the restoration of the “indestructible unity of life in state and church, in the nation and family”. He saw this unity as having been fractured by industrialism and secular thought. Wichern envisioned the Inner Mission as an essential counterforce, stepping into the breach where the state was “impotent” and the church was “silent”.

Together, these two mindsets—Chalmers’s surgical, morally rigorous localism and Wichern’s grand, nation-unifying vision—created a powerful and holistic approach to urban ministry. Chalmers and Wichern laid much of the theological and theoretical foundation for the city mission movement (and Inner Missions), which were later adapted to be more effective and practical by catalysts like David Naismith, the founder of the City Mission movement. Naismith later started City Mission Societies in the United States. Though none survived to today, he helped spread the vision. That vision enabled Jerry McAuley to found the Water Street Mission in 1872 launching the rescue mission movement in the US.

The Blueprint in Action: A Comprehensive Social Safety Net

The early City Mission Societies and Inner Missions were not just focused on evangelism; they were building a comprehensive, parallel social infrastructure. Each City Mission Society would choose their own services to provide, but across the whole movement, the breadth of their work was astonishing:

Evangelism and religious services were the primary focus encompassing everything from street preaching, Bible classes, character building, scripture distribution, missionary training, and prayer meetings to the distribution of millions of tracts.

Relief Services, including shelter in lodging houses and orphanages, sustenance through dining halls and coal distribution, clothing provision, child day care, aid provision, food provision, and crucial health services via free medical clinics and hospital visitation. This also included prison ministry, aid for the elderly, blind, crippled, insane, the homeless, refugees, immigrants, pregnant women, infants, fallen women, alcoholics, orphans, sick and dying.

Education and skill development were central, with programs ranging from kindergartens, to primary education, school planting and literacy instruction to vocational and industrial schools teaching practical trades, all aimed at fostering self-sufficiency and building character.

Advocacy and social reform, campaigning against perceived evils through the temperance movement, pushing for prison reform, and working to improve housing and labor conditions.

Community building and fellowship, creating spaces like community centers, clubs, museums, libraries, sports, concerts, gyms, billiard rooms, alcohol-free hotels and mutual aid societies to foster social bonds. This work was highly targeted, with specialized care for specific populations including missions for sailors and immigrants, homes for the elderly, and rescue work for other vulnerable groups.

Case management, outreach, and house-to-house visitation including careful investigation of individual circumstances, and personal support to ensure assistance was both effective and appropriate.

Their foundational belief was that indiscriminate giving, without requiring change or effort, fostered dependence and created a “pauperized humanity”. They believed true compassion required demanding moral transformation as the only path to genuine independence.

The Strategic Genius: ‘Society’ vs. ‘Mission’

Here lies the single most important and often overlooked innovation of the first wave: the distinction between the “Society” and the “Mission”. The City Mission Society was the strategic headquarters. It was a non-denominational coalition of pastors, civic leaders, and laypeople who came together to address the needs of the entire city region, transcending parochial and denominational divides. Its purpose was purely strategic and macro-level. The Society’s job was to:

Survey: Conduct a comprehensive analysis of the vast and chaotic needs of the city.

Synthesize: Turn that raw data into a unified, strategic Protestant response.

Fund: Raise dedicated funds at a scale no single church could manage.

Incubate: Found and develop new, specialized ministries to fill the specific gaps they had identified.

The Society was, as one source puts it, the “war room” for a multi-front campaign against systemic poverty and spiritual destitution. The individual City Mission, on the other hand, was the tactical operating unit. It was the “boots on the ground,” a specific, service-oriented ministry born from the Society’s strategy.

The Great Specialization: Why Our Work Looks the Way It Does Today

If this “first wave” was so comprehensive, why do modern rescue missions and city missions often have a narrower focus primarily on evangelism, addiction and homelessness? The answer lies in the rise of a major competitor: the modern welfare state.

It’s worth noting that there were a wide range of services provided by various City Mission Societies and European counterparts that very few realize were pioneered by the City Mission (and Inner Mission) Movement including the nursing profession (Florence Nightingale was trained through the Inner Mission movement), widespread hospital systems and widespread public libraries. In addition, Goodwill Industries was founded out of the Boston City Mission Society in 1902 by Edgar Helms, although it has since become entirely secular.

Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, governments began to gradually take over the functions that the societies had innovated: child welfare, public health, general relief, and standardized education. The history of this displacement of faith-based services for government services in the United States is well documented in The Tragedy of American Compassion by Marvin Olasky. However, the government adopted the functions while systematically rejecting the underlying philosophy.

The system shifted dramatically. The society model’s focus on personal investigation, affiliation, and moral change was replaced by the state’s focus on entitlement, depersonalization, and bureaucracy. Any attempt to assess character or demand reciprocity—the very heart of the Chalmers model—was increasingly viewed as judgmental and an affront to dignity.

This forced the city mission movement into what could be called a “strategic retreat”. As the state occupied the fields of general relief, the movement concentrated its efforts on the “high ground”—the areas where purely material solutions were clearly failing and where their core competency of spiritual transformation was still demonstrably required. Those areas were, and still are, chronic homelessness and addiction.

One way of characterizing it was that City Mission Societies were organizations that were innovating with a tremendous range of services/programs. Over time, some of those programs turned out to be more successful than others, and many programs that were initially successful were slowly displaced by the rise of the welfare state. What we now call City Missions are largely a much smaller set of programs that proved themselves effective and sustainable in the longer term. largely centered on evangelism, homelessness and addiction.

Our modern Rescue Mission & City Mission Model is a direct result of this history, essentially a specialization of the previous more comprehensive vision. We continue the work of combining evangelism and social services because we operate from the foundational belief that for those trapped in the deepest cycles of dependency, only a profound change of heart can lead to permanent self-sufficiency. As the London City Mission still professes, the “old-fashioned gospel of divine grace” is the real dynamic to lift the world, and there is “simply nothing to take its place”.

Reclaiming Our Blueprint for the 21st Century

The City Mission Society of the first wave was more than a charity. It was a strategic, holistic, city-transforming engine. It dared to blend robust social action with uncompromising moral expectation. It saw no division between saving a soul and reforming a citizen. It built a comprehensive social safety net because its leaders believed they were restoring the “indestructible unity of life” that God intended.

As we lead our ministries today, we can draw immense wisdom from this forgotten blueprint. It calls us to think bigger—to be not just providers of services, but strategic headquarters for urban transformation. It challenges us to ensure our compassion is always discerning, always aimed at the ultimate goal of true internal and external independence.

And it leaves us with the same profound question Wichern and Chalmers faced. Echoing the conclusion of the podcast that inspired this reflection: Where are the gaps now? In our own cities, where do the family, the state, and the established church currently fall short? And what new, innovative structures and methods might God be calling us to build to fill them?

For more information, listen to the podcast episode for this article and research notes for this article.