Why read this article? Learn about how:

David Nasmith launched the City Mission movement, starting almost 60 missions in 13 years

Innovation Theory can be applied to Nasmith’s innovations to explain why it was successful

The global City Mission movement continues today

The words “Union” and “Central” in many mission names today relate to the early City Mission movement

Don’t have time to read this? Listen to the Podcast on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Others

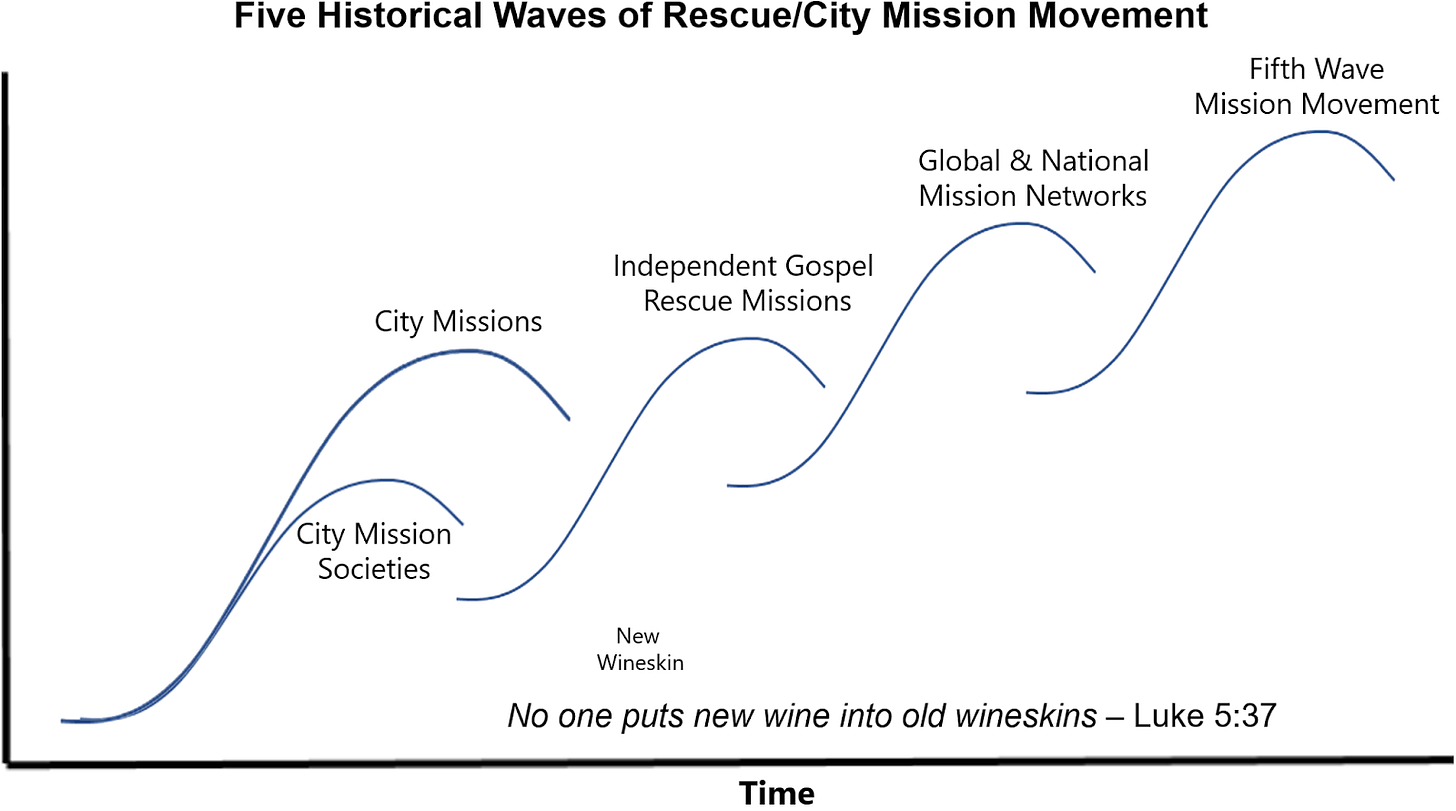

This article is the second in our series focused on the five historical waves of the city mission and rescue mission movement. The last article covered the first wave in How City Mission Societies Formed the Basis for the Rescue Mission Movement. This article focuses on the City Missions as the second wave of the movement.

The first article explained that City Mission Societies were innovative Christian parachurch ministries that provided a tremendous range of services/programs. Over time, some of those programs turned out to be more successful than others, and many programs that were initially successful were slowly displaced by the rise of the welfare state. What we now call City Missions typically offer a much smaller set of programs that proved themselves effective and sustainable in the longer term, largely centered on evangelism, homelessness and addiction.

This article focuses on the City Missions as the second wave of the Rescue/City Mission Movement. The first wave (City Mission Societies) and the second wave (City Missions) largely emerged at the same time, as shown in the diagram below. However, I believe City Missions should be characterized as a second wave because there are very significant differences between the vision and mission of early City Mission Societies and what we now call City Missions.

David Nasmith’s Story as Founder of the City Mission Movement

David Nasmith is widely credited as the founder of the City Mission Movement. We covered his inspirational story in more detail in S1E2. David Nasmith & Jerry McAuley: The Interconnected Histories of the City Mission and Rescue Mission Movements.

Here is a quick recap of his story for those who missed that podcast episode. Nasmith initially tried multiple times to become a foreign missionary, thinking he was headed for Africa or the South Seas, but he got rejected. Apparently, this was due to a lack of formal education, which is ironic given his later work. However, that rejection basically redirected his energy toward meeting the needs right in front of him. He ended up inspiring or founding a tremendous number of Missions, both in the UK and crucially, influencing efforts in America. This shows that your mission field might be closer than you think.

Nasmith’s ministry began in Glasgow, Scotland in the early 1800s. The Industrial Revolution was causing tremendous disruption, socially and economically. Glasgow and cities like it were exploding in population. This meant terrible overcrowding, grinding poverty in the tenements, and, crucially for Nasmith, a sense that many people were spiritually lost and relationally adrift. Nasmith, just 27 years old, was already active in Christian circles, youth groups, and supporting Bible societies, and had sought to be a missionary overseas. But when that didn’t happen, he focused directly on addressing Glasgow’s problems with the Gospel, in word and deed. Therefore, he founded the Glasgow City Mission in January 1826 as the world’s first city mission.

What made the Glasgow City Mission so different from other urban ministries before it? If you analyze the key characteristics of the City Mission movement, several innovations stand out:

Interdenominationalism: creating a parachurch space outside formal church structures. Previously, efforts like this were run by a particular denomination, like the Church of Scotland or the Baptists, and led by ordained ministers. Nasmith wanted Christians from all denominations working together to serve the urban poor. That was pioneering.

Holistic ministry: the whole person matters—body, mind, and spirit. His aim was to offer Christian care to any in need, whatever that looked like. Spiritual care was central—visiting the poor and most importantly, sharing the Gospel. But his vision went way beyond that. It was about physical, emotional, and spiritual needs, all interconnected.

Dual focus on evangelism and practical help, not choosing one over the other.

Lay leadership, not requiring ordination using paid workers. Leaders were often from the working class themselves so they could relate to those in poverty. Nasmith’s lack of ordination, education and working-class background all were factors that led to him being rejected by established churches sending foreign missionaries. This rejection ultimately led to one of the movement’s key strengths by removing unneeded barriers to leadership of city missions.

Focus on the marginalized: the poor, the unchurched, and prisoners, those often overlooked.

Nasmith’s innovations could largely be summarized as essentially inventing the modern parachurch model focused on alleviating urban poverty. In our podcast episode S1E4. Origins of the Rescue Mission Movement in the History of the Parachurch & Christian Charity, we explain that the City/Rescue Mission movement is a part of a larger parachurch Christian charity movement with a 2,000 year history.

In “The Two Structures of God’s Redemptive Mission”, the famous missiologist Ralph Winter explained that the Protestant Reformation, in its necessary and zealous hostility toward the corrupt state of late-medieval monasteries, made a critical error: it effectively discarded the structure of mission-focused societies (often based in Monasteries), which he saw as the historical equivalent of modern parachurch organizations. Because this form was lost to history, Nasmith essentially reinvented it. It just goes to show that when God wants something done, he will raise up people to correct the mistakes of past generations.

It’s worth noting, though, there were early prototypes of organizations doing work similar to City Mission Societies and City Missions. The article Why Glasgow’s City Mission Society & City Mission Was Truly the First explains that while each of these prototypes included elements of the City Mission Society model, they should not be considered the first City Mission because they did not include all the essential innovations that defined the new model and made it replicable (interdenominational, lay leadership, etc.).

Using an airplane analogy, these organizations might be considered analogous to early gliders, hot air balloons or blimps that predated airplanes. Such flying machines were significantly different from the Wright Brothers’ first airplane. Only when the Wright Brothers had achieved the first sustained, controlled powered, heavier-than-air flight could their innovation be replicated to enable a new era of travel. Similarly, it took Nasmith’s innovations to launch the next era of the Rescue/City Mission Movement.

Diffusion of Innovation Theory and City Missions

To understand the City Mission movement’s history, this article will use the analytical lens of Diffusion of Innovations theory, a framework developed by sociologist Everett Rogers. Diffusion of innovations theory is valuable because it can help identify the common patterns of what made previous innovations successful, so we can discern what might be needed to successfully innovate in the next wave.

In other words, if we study the innovations that enabled other generations of airplanes, we are more likely to be able to identify the innovations needed for the next generation of airplanes. While some might argue that it is overly theoretical and detailed to take apart the airplane in this way, it is only by examining how the parts came together to make them work that we can better understand how to improve them.

Similarly, it may almost seem sacrilegious or disenchanting to take apart various innovations that came together to enable movements of God to understand how the pieces fit together to make them work. This doesn’t discount the miraculous hand of God to understand the mechanics of historical movements of God any more than does the field of medicine understanding how the human body works discounts the miracle of life.

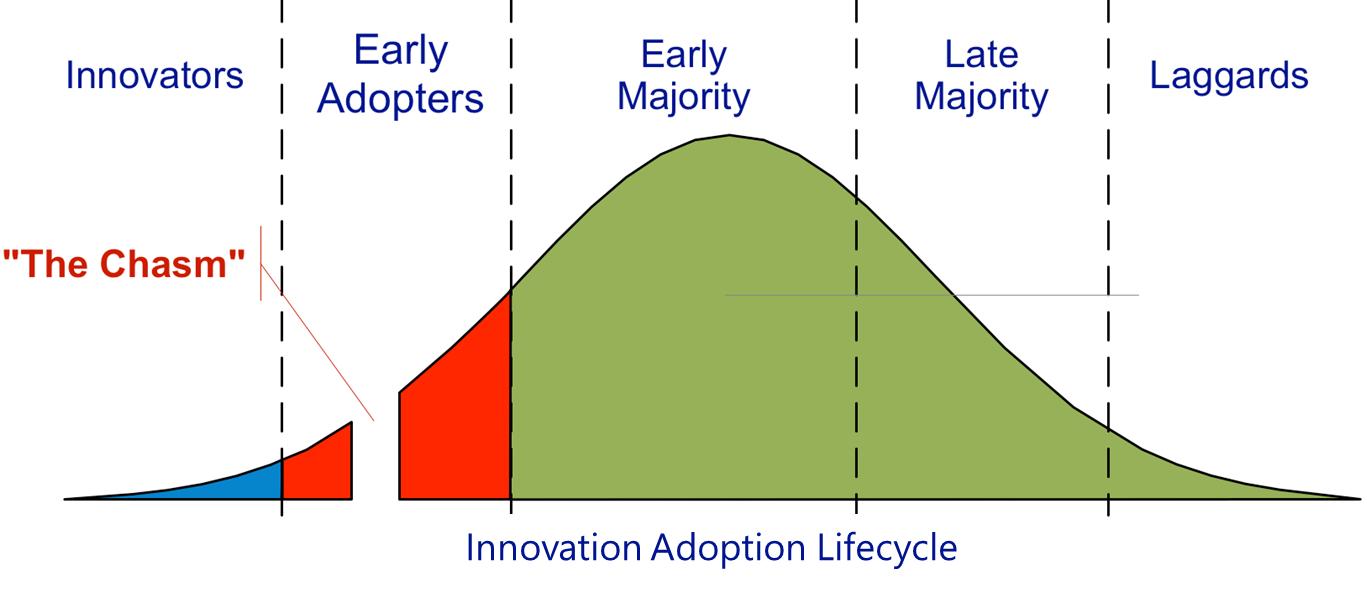

The Innovation Adoption Lifecycle is the most significant aspect of Rogers’ theory. Rogers identified a pattern that as innovations spread, people adopt them at different rates as shown above, falling into categories of Innovators, Early Adopters, the Early and Late Majority, and finally, Laggards. Similarly, often those leading innovation are often most effective at leading in one or two of these stages. Geoffrey Moore later popularized the term “The Chasm” to point out the critical gap that separates the early adopters and innovators from the more cautious mainstream market.

David Nasmith as the Innovator-Diffusor

In the context of the Innovation Adoption Lifecycle, David Nasmith was the master of the Early Adopter Stage of the movement. He was the crucial figure who took the strategic vision of the City Mission Society and translated it into a replicable, tactical model of the City Mission. Deeply influenced by the missionary zeal of his pastor, Greville Ewing, and the systematic approach of Thomas Chalmers, Nasmith founded the Glasgow City Mission in 1826 and the London City Mission in 1835. Arguably, Chalmers and Ewing laid much of the theoretical and theological foundation as innovators providing early prototypes, but Nasmith’s innovations were central to making it replicable for early adopters.

Nasmith was a master of diffusing innovations. He recognized the genius of Chalmers’ methods but also the barriers to their adoption. Chalmers’ model, reliant on a large corps of volunteers from a single parish, was difficult to replicate. Nasmith adapted the model by using paid, full-time lay agents—who were more dependable than volunteers—and by making the mission inter-denominational, freeing it from parochial constraints. This created a more “adoptable” innovation. Nasmith traveled tirelessly and started almost 60 City Missions including missions in Scotland (1), England (1), Ireland (20), the USA (16), Canada (15) and France (2). This is even more remarkable considering that he did all this in a 13-year period before he died at age 40.

Characteristics of Successful Innovations and City Missions

From the perspective of trying to develop future innovations, one of the most helpful aspects of Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory is his list of five key characteristics of innovations. Rogers found that these determine the rate by which a new idea is adopted.

Relative Advantage: The degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes.

Compatibility: The degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters.

Complexity: The degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use.

Trialability: The degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis.

Observability: The degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others.

Nasmith’s City Mission model scores high on Rogers’ factors:

Relative Advantage: Compared to a volunteer-based model, the use of paid agents was more sustainable and dependable. Furthermore, these agents were often from the working classes themselves, giving them a high degree of cultural similarity, or “homophily,” with the people they served, which increased their relational effectiveness.

Compatibility: The model’s inter-denominational character was highly compatible with the cooperative spirit of the evangelical movement. Its focus on the “unchurched” at home resonated deeply with the existing missionary impulse.

Observability: The work of city missionaries was meticulously documented in detailed annual reports, which were used for fundraising and promotion. These reports made the model’s activities, challenges, and successes highly visible to potential supporters and imitators across the globe.

When we apply innovation theory to understanding the mechanics of why previous waves of the City/Rescue Mission movement were successful, we can then apply the same principles to evaluate what characteristics to look for in future waves. This doesn’t discount the role of God in empowering movements. It’s just an extension of how we look for “best practices” on how we innovate as nonprofit ministries.

First Three Waves: From the City Mission Societies to City Mission to Rescue Missions

In the first article in this series, we saw the City Mission Society wave represented a huge range of services to address the spiritual and social problems emerging from rapid urbanization.

This is a common pattern when new waves of innovation arise to address a new opportunity, often there are a plethora of potential solutions. Some work, and others do not. Eventually there are a few models that succeed. Contrast these pictures of early attempts at flight (which are drastically different) to the first airplanes (which are much more similar in design).

City Mission Societies could be viewed as early attempts to address the spiritual and social problems of rapid urbanization (like early attempts at flight), while what we now call City Missions emerged as models of what worked and was sustainable (like the first viable airplanes). There were a wide range of ideas for flying machines, but only a very few designs actually emerged as viable. Similarly the City Mission Societies article explains that these societies offered hundreds of services across various mission societies, but only a much smaller subset became sustainable in the long-term. In this analogy, Nasmith could be comparable to the Wright Brothers (who built and flew the first successful airplane).

Like most people skilled at leading the Early Adopter stage of the innovation cycle, the primary critique of David Nasmith was that he was often spread too thin. This likely the primary reason for his early death at 40, which left his wife as an impoverished widow with five young children. Fortunately, those who followed him took up an offering to provide for his widow. His pattern of being spread too thin also likely contributed to the fact that the vast majority of the missions he founded were not sustainable, so only a few still exist today.

This is not to underestimate his impact on the movement. Likely his most important contribution was spreading the idea and replicable model of city missions. While none of the city missions he started in the United States survived, the idea and model of city missions that ultimately became the rescue mission movement in the United States clearly came from David Nasmith.

Ultimately, that vision gave birth to the third wave of the movement, which was initiated by Jerry McAuley - the founder of Rescue Mission Movement in the United States. That story will be the subject of our next article in this series.

City Missions Today

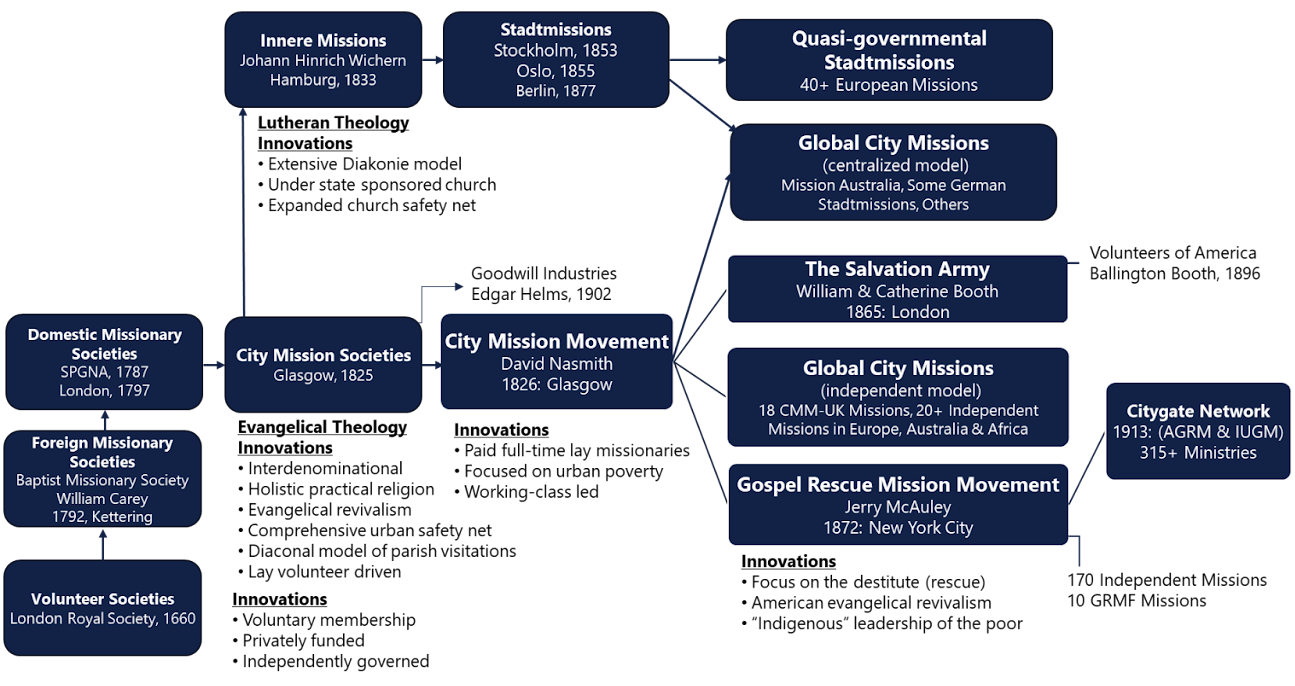

Today, the global City Mission Movement outside of North America could be divided into four branches, as shown in blue boxes in the upper right of the City Mission/Rescue Mission Family Tree here and in the diagram below.

City Vision has compiled this Directory of Rescue Missions & City Missions (spreadsheet). A summary of those branches of the movement is as follows:

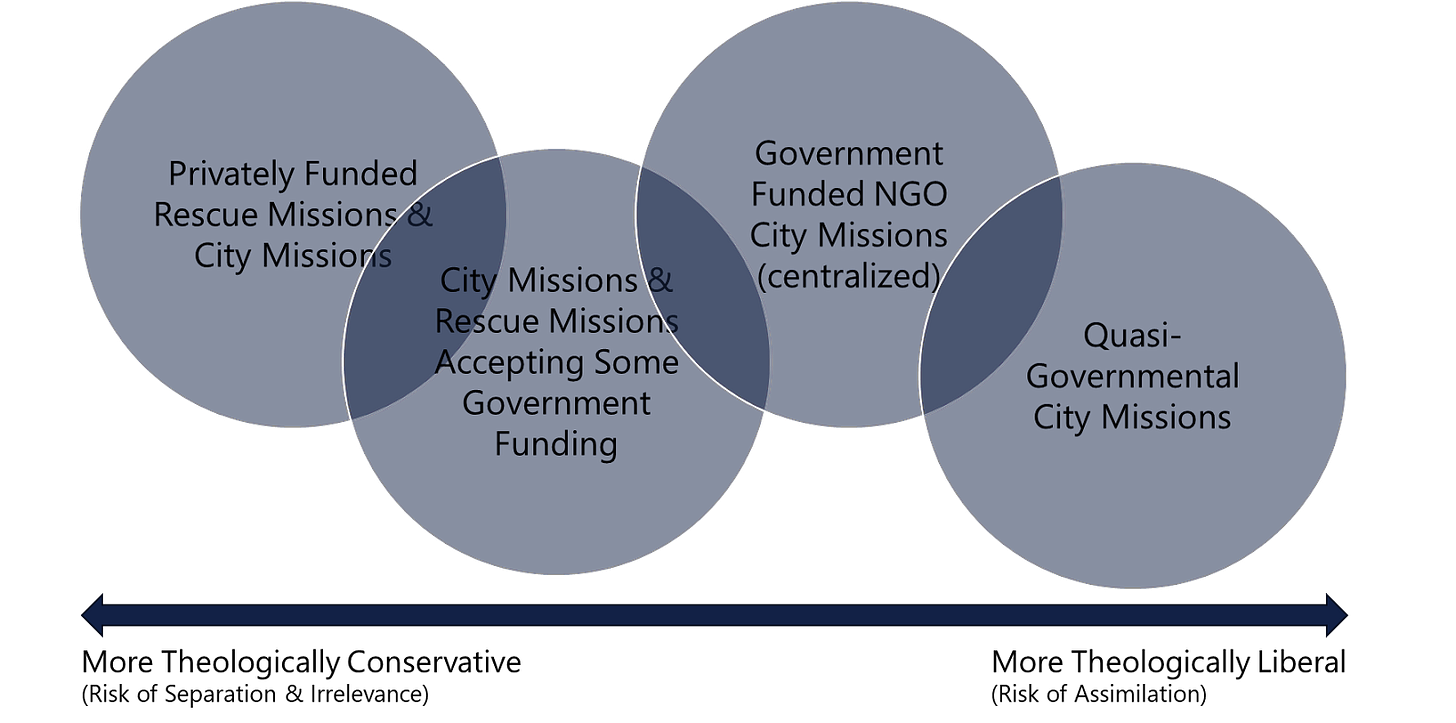

Independent Global City Missions: These include 18 UK Missions affiliated with the City Mission Movement UK and 20+ Independent Missions in Europe, Australia & Africa. Typically these take little or no government funding.

Centralized Global City Missions. These typically are local missions that are a part of a national organization. This includes some Mission Australia and some Stadtmissions in German and other continental European countries. These typically receive a large proportion of government funding (often the majority).

Quasi-governmental Stadtmissions. These include 40+ missions in continental Europe that are a social services arm of state-sponsored churches, most often associated with Lutheranism.

The Salvation Army. The Salvation Army, while often operating independently of the rest of the City Mission movement, clearly emerged from God’s larger City Mission movement, but with its own distinct model.

All City/Rescue missions can also be categorized into a typology as shown below. Our presentation A Typology of Faith Based Organizations provides a more detailed explanation of a similar typology that is generalized beyond the city/rescue mission movement. It’s worth noting that the theological and cultural difference between Privately Funded City/Rescue Missions and Quasi-Governmental City Mission are vast, so it is arguable that they are entirely different movements at this point.

In the next article in this series, I will explain why the terminology for the movement outside of North America’s missions continued to be called City Missions, but in North America the movement became called the Gospel Rescue Mission movement (or Rescue Mission movement for short). This article will explain that this is not simply a difference in terminology, but also a reflection of a unique wave of the movement emerging in the United States.

City Mission Societies & Why So Many US Missions Use the Words “Union” or “Central” in their Names

There is another aspect of the transition from City Mission Societies to City Missions that relates to adopting the legal form of a nonprofit corporation with a board. The core idea behind City Mission Societies is that the societies were gathered as a citywide interdenominational group of pastors and churches (often with an evangelical core ethos) that came together in a centralized effort to serve the whole city. Often the number of churches and pastors involved made the society closer in size to an association (often with 30+ leaders) rather than the typically much smaller nonprofit board (usually less than 12 people).

As the legal form of nonprofit corporations became more popular, many City Mission Societies (and later Gospel Rescue Missions) formed nonprofit corporations, which required having a legally recognized board of directors. Over time, it seems that the legal function of the board of directors became the primarily governing paradigm rather than the idea of an interdenominational society of pastors and churches collectively serving the city. It seems that something of the original intent of these missions serving as a collective action of churches was lost to history over decades.

This is highly relevant today, especially in the United States where the most common words used in the names of missions, aside from the word “mission”, have been “central,” “union,” and “rescue.” Today there are many missions in the United States that still have the words “union” and “central” in their name. However, they don’t know the full significance of the history of those parts of their name, and how it ties back to the centralized collective action of churches in serving their city, dating back to the concept of City Mission Society.

For many missions, fundraising, business success and influence drive who is on their board of directors. If you look at their board of directors, they often represent the “who’s who” of successful Christian business leaders in their city, but all too often they have little or no representation of pastors on their board. Regardless, the board of directors for most missions today look very different from the citywide interdenominational alliance of pastors/churches of City Mission Societies.

This has profound implications on the trend of potential secularization of missions. Pastors and business leaders have very different perspectives, in many ways help to balance each other out. Missions with boards too dominant on the business side often tend to not recognize the significance of the secularization threat as much and usually do not have the training to address it. A best practice for boards is to be intentional about this proportional split of board members.

In some cases, I have seen Union Missions and Central Missions with no pastors at all on their board. I’ve often heard those in the mission movement criticize the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) for not having anything Christian in it. For some of these missions, while they still clearly retain the Christian aspects of their mission, there is very little left of the “Central” or “Union” aspect. While some might argue that this is an argument for rebranding and removing those parts of their name, I personally believe that losing the citywide alliance of pastors/churches as a central aspect of their mission would be mission creep.

This is just one more example of as we work to discern new innovations and methods that God may be using, it is equally important to understand the larger history of which we are all a part.

For more information, listen to the podcast episode for this article and research notes for this article.